“Mail From Medellín”– Barbet Schroeder

(Mail sent while making ‘Our Lady of the Asssasins’ in Medellin)

–While we prepared and filmed Our Lady of the Assassins, shot in absolute secrecy, I lived from May to December 1999 in Medellín, Columbia. The city of eternal spring, the city where the kindness and courtesy of another time—that of my childhood in Bogotá—lives on to this day. It’s also a city obsessed with order and cleanliness, a city full of energy and happiness.

There is of course another facet to it which can be summed up in figures:

– Thousands of armed gangs, each of them with 4 to 200 members;

– 95% of crimes go unpunished—many more than in the Far West when it was still a lawless land;

– 15 deaths per day, 30 on weekends and holidays.

Everything is played out in the “Communas”, poor neighborhoods created by “invasions.” Rudimentary brick buildings, magnificent views on to the rest of the city. The police only enter the communas in case of dire necessity and then in droves. The paramilitary and the guerrillas dispute areas of influence by creating or taking control of certain gangs. I’ve collected here in chronological order some e-mails —quick snapshots —I sent once or twice a week to Fernando Vallejo and some friends during this time.

*****

Little Jennifer’s Birthday

I’ve just understood why children start sniffing glue: it staves off hunger. They end up doing it all day long and die within three to four years.

There’s a party in the streets of the Barrio triste for little Jennifer who looks twelve years old because she sniffs glue but is celebrating her fifteenth birthday. It’s a Colombian tradition to celebrate one’s coming of age with a party and dances, particularly a waltz with fifteen successive partners. Those who were there to dance with her: a little boy sniffing glue, a young professional killer, a policeman, a man who’d had both his arms cut off when he’d fallen asleep drunk on the railroad tracks. Jennifer held onto the stumps, smiling absentmindedly. What a waltz! People gave her as a present a dress and a bag for her glue bottle made of the same cloth

Hold-Up

Very first scouting. I’m filming Boston Park and the house where Vallejo was born with a small digital camera when I hear yells behind me. It’s my friend Eduardo screaming out a slew of insults: “motherfucker, gonorrhea,” etc. He runs and stops in the middle of the street pretending to load his cellular phone as if it were a black gun. A young, well-dressed man had just stuck a 9mm semi-automatic pistol in Eduardo’s stomach while grabbing his cell phone out of his back pocket. Eduardo had ripped the phone out of his assailant’s hands and was now pretending it was a gun! The young man takes a few steps toward me, people are starting to notice, he puts his right arm behind his back. He wants the camera. I finally see a chance to use my small paralyzing pepper gas spray. Holding the camera, my arms outstretched, I tell him to come and get it. He thinks it over, turns around and leaves. The thing is i didn’t see the gun. He must have thought he was dealing with two dangerous lunatics, and that it was too risky.

He didn’t depart empty-handed—he’d still had enough time to steal our driver’s gold chain while threatening her with the gun and telling her everything was going to be alright.

Bogotá

I read in the local paper that living here, breathing normally, is like smoking two packs of cigarettes per day.

There’s a new paranoia here about taxis mugging you like in Mexico City, sometimes with the help of fake cops. Remedying the situation by calling a cab over the phone has not proven to be safe either; gangs intercept the radio messages and send one of their own taxis instead, etc, etc. But that’s not the worst of it: sometimes an accomplice comes out of the trunk, gun in hand, by swinging open a section of the back seat.

Just driving along the Septima, one of the main avenues, has become a dangerous adventure. Last night, on a stretch of road less than half a mile long, I counted over seven large open sewers whose lids had been stolen. They’d been left like that without any sort of indication—gaping open, waiting to destroy a car or kill a motorcyclist.

Father’s Day

Today I met the mayor of Medellín.

He’s very worried about a new armed gang made up of FARC dissidents operating in the Pilarica neighborhood and headed by a female doctor who is apparently out of control and very bloodthirsty. Four policemen were seriously wounded last night by her gang.

While we were in his office he found out that one policeman had died. Alittle later another phone call:a commando of seventeen members of the Las Terrazas gang (from the Manrique neighborhood)has burst into the San José Hospital to free a terrorist and a very dangerous assassin who had been injured and brought there from the high-security prison.

Last Sunday, on Father’s Day, there were thirty-four deaths. That same day the opening of the Poetry Festival drew a larger crowd than any soccer match ever had in the city’s history.

The casting’s going very well—in just a few weeks we have already found two possible boys.

These fifteen-year-old criminals’ vitality and angelic good-looks, the very studied elegance of their clothes and their way of considering their short lives like that of a butterfly are irresistible. The ones that survive talk like retirees—they’re 21 years old.

Tango

I spent the afternoon in the Diamante Commune where we’re going to shoot some scenes with Alexis’s mother. There was a huge popular party organized by my friend Papa Giovanni to watch seven to nine year-old kids dancing tango. These very young couples’ gestures were impeccable and their extremely elegant costumes shone under the sunlight, the crowd clapped louder with each sexy gesture. Up above, very close by, a dozen vultures glided. A bit higher up on the hill youngsters from the neighborhood gang watched this scene of family cheerfulness indifferently. They woke up a bit when their friends in the rap group started singing their message of violence. Down below, in the distance, the whole city rises up on the other side of the valley.

A dead man on the street corner

Last night I went to eat patacón (fried bananas) at a fast food place near the Éxito. Leaving the house I turned left and after I’d taken a few steps I stopped when I heard two gunshots and saw two well-dressed women running crouched like soldiers in a war movie, except in high heels. After waiting a moment I walked towards Laureles Park to see what had happened: an old car in the middle of the street with a motionless driver and passersby coming out of their hiding places to look at and approach the vehicle.

When I got back half an hour later, there was nothing left but a small pile of smashed glass from the windshield on the pavement and I had the impression I’d made it all up.

Another corpse

Last night before dinner, today before lunch. At noon I was walking like I do everyday with my friend Eduardo to go eat five minutes away from here. Yesterday he had gone to the morgue and at a red light recognized the driver and van that picks up bodies. Sure enough, not too far away, there was a very young man on the ground surrounded by curious onlookers and policemen…

When I get back, less than half an hour later I again think it was all a dream: no trace of blood and children are playing right where the body had been.

An hour ago, an intense shoot-out and screaming in my street: neighbors are firing at a bicycle thief. Without hitting him, I hope.

The violentologist

I got back from Bogotá a day earlier than planned and the Vallejo family had taken advantage of our absence to put up in our house a French violentologist who was reading a paper at the university. My friend Eduardo sounded the alarm when he realized the violentologist was a marked man who had received threatening letters both from the FARC and the paramilitary and that many of his Colombian disciples had been killed over the last few years. He himself had asked the Vallejos not to be lodged with the other professors in another apartment. We unfortunately had to ask him to leave immediately. We are here for months while he is only here for a couple of days. And we speak French just as he does. That would be enough to get us killed.

The Prince

A few days ago I was having a drink by myself at the Café Lebon bar by Lleras Park in the Poblado. I was chatting with my friend Aleja, a philosophy student who manages the bar one night out of two. A thirty year-old guy, very expensively dressed, tall, skinny, mustache, a scar on his cheek, very dark-skinned, starts talking to me—he has a very strong lower class accent. He wanted to know where I was from and what I was doing in Medellín. I tried to cut our conversation as short as I could. He left to make a phone call (someone saw him). A few minutes later two black Mercedes arrive with seven scary thugs who take their seats on the terrace. The first guy comes back to talk to me again. He tells me that he’s going to France next week and that one of his friends here presently lives in France and would like to take me out for a drink. He calls himself “The Prince.” I refuse and go sit on the terrace with two women-friends of mine who were there. They are soon bothered by the insistent stares of these mafiosos I had my back turned to. We decide to go to the Café Berlin, right next door, in their car. From the bar, Aleja is horror-stricken as she watches the eight guys follow me intensely with their eyes. As soon as I get into my friend’s car, they all get up at once and jump into their Mercedes. Aleja ran to the phone to warn all my friends who desperately searched for me throughout the neighborhood with the help of the police before finding me an hour later calmly seated in a dark corner of the Café Berlin. Without realizing it we had taken such an unexpected route to go so close by that no one could have followed us. Or else nobody was following us and the whole thing was the effect of the pervading paranoia…

Yesterday in Bogotá a gang of criminals was arrested—they kidnapped people and sold them to the guerilla, who would then hold them for ransom.

Manrique

Two scenes in the movie take place in Manrique, a neighborhood that because of the Las Terrazas gang, has become one of the city’s most dangerous. Papa Giovanni has organized protection for us so we can scout the neighborhood but I immediately realize that even he is ill at ease. He introduces us to a twenty-two year-old gang boss, a survivor, slightly fat, crew cut, blue, unblinking eyes. He’s got a strategy to never, ever look anyone in the eye. Very, very calm, his gestures measured. You get the chilling feeling that he is staring at piles of corpses behind the person he is speaking to. He never smiles. Even Eduardo who’s very funny and who’s used to this kind of character can’t make him laugh. There’s another guy who laughs nervously all the time—the gang leader’s henchman, a sicario (hired assassin), very dark-skinned and full of tics. In veiled terms, always laughing, allusively, he brags about a being bad,something about a chainsaw. We wanted nothing to do with it, we wished we’d never met them, we want them to forget they ever knew us.

We go all over the neighborhood. I discover another side to the gangster’s personality: he tries to pick up all the girls by giving them orders—”You, come over here!”—or by complimenting them while making lewd noises. Sometimes the killer joins in. The girls, even very young ones, already know it’s very dangerous to react in the slightest way and keep walking. The gang boss seems extremely intelligent, asks the right questions. He must have graduated from crime school magna cum laude and only gets involved in major hits. In passing, he wants to know how much the film equipment we brought is worth.

We won’t set foot in Manrique again and we won’t ever ask Papa Giovanni to show us around another neighborhood that isn’t his.

As a goodwill gesture at the end of the day we take them for fried chicken to Mario’s, the fast-food place in front of Carlos Gardel’s house. When it is time for the gang boss to get his wages he tells us in a terrifying tone: “I’m very curious to find out how much you think I’m worth.”

While Eduardo is writing the amount on a receipt, I say: “I think he’s only putting down zeros,” Phew! I’ve finaly managed to make him laugh.

As we get ready to leave the restaurant he doubles back to replace the chairs at our table in perfect order, like a meticulous maniac, as if we had never been there.

The bomb

I have the awful feeling the country will once again be the focus of world media because of this booby-trapped car filled with a hundred kilograms of dynamite that killed twelve people the day before yesterday. Though in fact we weren’t in any danger, as the bomb was aimed at a military target we never even get close to. For instance we take detours to avoid passing by police stations. The flower festival began yesterday. The bullring was empty for the bullfight —lack of advertising, bomb-related trauma—and the rejoneador (a bullfighter on horseback) couldn’t fight: his horses were kidnapped yesterday on the Bogotá–Medellín highway.

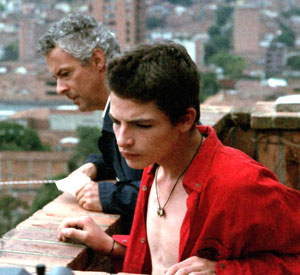

Anderson

That’s it, I finally met Anderson. I’d seen a video of him and sent everyone looking for him through the city for the last fifteen days. He is absolutely extraordinary. Ambiguous, angel and devil, very charismatic—a sixteen-year-old, streetwise, Montgomery Clift type. His acting needs some work but he’s bright and the camera loves him. He lives with his thirteen year-old brother in a Commune very high up in the hills controlled by the militia tied to the guerillas. We try to put him up in town but he doesn’t want to move because his mother, who’s in prison, calls him at a phone up there. He sells incense on the street and has just finished a three-month jail sentence for burglary. Last night with three friends of his he assaulted a passerby,they split the equivalent of fifty dollars. A little later the police stopped them after they’d already spent the money and made them give their victim their shoes. He had to go home barefoot: a two-hour climb to get to the end of the La Sierra barrio, created after a recent “invasion.” Tomorrow I’m taking him to see a doctor and we’ll look for an apartment for him near his little brother’s school.

The Frenchman flees in panic

A hard blow today, certainly not the last and I can’t help but laugh about it. My production manager, who had left for Paris for a few days, has just pulled out; he doesn’t want to come back as planned, he was too scared here and didn’t dare tell me. He gave me the key to his locker when he left. I’ve just opened it: practically empty, his treason was premeditated! From now on, I will be the only foreigner on the crew!

Exchanging money

A weekly ordeal. The Banco Comercial has the best rate and anyone who has large sums of money to exchange goes there. You also always run into at least three motorcycles with suspicious-looking teenagers: clean-cut, American-style; baseball cap, short-sleeved shirt or jacket, blue jeans and sneakers. This often means: ready to kill, and there’s also often a policeman who keeps watch over all this and asks them for their papers. We get a cab to drop us off, but it can’t stop in front of the bank or next to it like the motorcycles do. It has to go around the block until we exit with the money which Eduardo (who also has his gun) and I have split the money evenly between us.

The first person we see upon entering is a uniformed guard with his finger on the trigger of an enormous pistol. Further in we see another guard with a special deluxe model shotgun and finally, right at the back, next to the teller where we exchange the greenbacks: a mini-Uzi held by an utterly motionless guard, his jaws clenched. Like all the others, his finger on the trigger.

Endless wait while the cashier counts the massive piles of bills twice. Right next to us a very long line-up for current accounts. Everyone’s favorite pastime: to stare and scrutinize every detail, every gesture of the few people lined up at the dollar exchange window.

When we exit the tension mounts by a notch. Eduardo waits outside while I stand inside. We’re never lucky enough to have our chauffeur (an ex-cop who borrowed a cab) come around at the right time. Again, we have to wait.

But the worst has yet to come. It’s when we drive off, the two of us looking intently out the rear window to spot any suspicious motorcycles. We also have to watch out for cars, and then go through a maze of small deserted streets to make sure no one is following us before emerging suddenly onto a highway and taking the next exit. Phew! But there are motorbikes everywhere… It’s not surprising the French production manager left, he had to live through this at least twice. I’ll be glad when will have a reliable local production company open an account, something that is strictly forbidden to foreigners in order to prevent money laundering.

Anderson blushes

Anderson blushes

Eduardo can “read” people by observing little details. He is in the front seat of the car and feels a thief looking at his Nike watch. That’s Anderson, sitting in the back seat beside me. Later, at the restaurant, he catches a glance again that lasted for a fraction of a second and tells him, gesturing as if he were taking off his watch: “You want it?”

Anderson turns bright red. Very sexy.

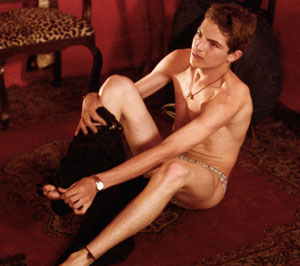

Wilmar

I jumped up and down with joy the day I found my Wilmar before leaving Medellín two days ago.

He’s very dark-skinned, from the streets.

He is perfectly, absolutely, unquestionably handsome and has a real natural talent for acting.

He isn’t as touching as Alexis who is more tragic, doesn’t act as well but has all the mystery of a true “star.”

In short, the film is really starting to exist and I’m more and more excited.

It is such a strange feeling to be back in the U.S. for a few days, safe and sound, after months of living on edge. Of course everything seems vapid and I’m anxious to return to Medallo.

The tests I did in Chicago didn’t turn out well. High-definition doesn’t allow us, as I’d thought, to film at night in the street with available light. At the risk of having it look too grainy, I’m going to try to do it anyway. This film doesn’t have to be polished.

Todo bien

Two serious problems the day before yesterday. We lost the most important, irreplaceable location—the apartment the film takes place in—, and two bikers caught up to our driver and threw a crumpled paper ball into the car, a note that read: “LOS PP’S QUEREMOS AL MONO TODO BIEN” (the PP’s want the foreigner, everything’s all right).

In Colombia receiving a note like this is often a death sentence. Now the paranoid atmosphere is guaranteed. On the bright side, we think it’s from a gang who are into extortion and not kidnapping. The dark side: it’s only the beginning, something else could follow like someone firing shots at the car or the house. Today a meeting with one of the country’s top “security analysts” who suspects… the chauffeur. We are waiting for the results of the graphology (writing samples) tests. Anyway, without telling the security specialist (you really can’t trust anyone), we have also established discreet contact with the police chief. Starting tomorrow he is lending us two cops dressed as civilians armed to the teeth who will follow me in their car as soon as I leave my new home which will be a true fortress. Officially I will keep living at the same address. I will never travel twice in a row in the same car, my drivers will also be security guards. On location starting tomorrow for the outdoor rehearsals there will always be a armored car ready to take me away! There are many other very funny details I can’t disclose before we finish shooting, and others I’ll never be able to or, at best, ten years from now.

The actors’ reading went fabulously well. The script is perfect and so are the actors. I am a happy man for the moment, now we just have to make the movie come to life.

Today I had lunch with the doctor who rented instead of us our main location of the apartment with the terrace . He was appalled by the fact that we had been able to find out who he was and had him summoned from Bogotá by a medical bigwig who could make or break his career. He is willing to leave the apartment he has just settled in! We now have to convince the agency to void the doctor’s contract. Not an easy thing since they already double-crossed us once.

Bodyguards

I don’t enjoy my new life with bodyguards but I maintain my perspective on things; it seems I’m a level-seven risk” (on a scale of ten). In any case it certainly impresses my young actor Anderson who spends his days and part of his nights with me.

My bodyguards are two young policemen, no more than twenty-four years old. I am in permanent radio contact with them by means of a little black object which is a combination cellular phone, beeper and radio. If someone suspicious like “The Prince” approaches and speaks to me I only have to press a little button and the whole security corps listens in on our conversation. They both carry guns, mini-Uzis and changones (sawed-off hunting rifles).

The first, Raul, is short, dark-skinned and fat, and the other, Leonardo, is skinny, blond and good-looking.

Leonardo has decided to become my friend and he’s very forward. He even went so far as to ask me to lend him my apartment in New York. The day before yesterday he asked me if I like Antioquian food. Only a complete boor would have said no, so I said yes, and besides I actually do. He then asked me if I wanted to have lunch at his place the following day. He insists I go alone which has made me experience a horrible inner conflict and led me to think about it in four differing ways:

1- It’s a trap—every kidnapping story involves a cop.

2- I have to go—it’s the least I can do for someone I make follow my rhythm of no more than six hours’ sleep per day.

3- I have no reason to feel obligated—he’s the one who’s exaggerating by putting me in this situation.

4- I’m naturally curious.

Number four eventually won out. A family atmosphere with a dash of paramilitarism. At least five statues of the Virgin. I now know all the technical details about the manufacture of home-made guerilla bombs.

Today we had lunch in the country, a beautiful house at the top of a hill. Before we ate, a pistol-shooting contest between Eduardo, Raul and Leonardo—I was quite proud to be at their level. We eat in the large living-dining room closed off from the terrace by a big bay window. Outside, Leonardo and Raul, their mini-Uzis dangling nonchalantly at arms’ length, watch us…

I hope they’re not too upset that my friend Eduardo forbade them to call him “La Rata” like everyone else does and that Anderson smokes pot in front of them.

For this evening they asked me what type of neighborhood I was thinking about going to (whether it was a hot spot or not), to know what kind of weapons they should take.

The tragedies of young actors. “Cobrar el muerto”(Avenging a death)

Anderson hadn’t told us about his recent problems with the law: he’s wanted for kidnapping and armed assault! We try to soften up the judge. In one of the cases they’d taken a cab driver hostage but the taxi had an alarm system that paralyzed the vehicle after fifteen minutes. Anderson and his friends found themselves in the open countryside in the middle of the night with a mob of taxi drivers(all comunicating trough their radios) who were about to lynch them; they were saved by the police, who then filed charges against them.

Juan David, who plays Wilmar, is also in trouble. He lives in the Bello Commune and he’s on a list—made by a group interested in “social cleansing”—of people to be executed. He should move today to an apartment we found him right next to ours. The day before yesterday, a rainy night, none of the members of his gang were on guard, watching out for the neighboring enemy gang who took advantage of the situation and sneaked into his best friend’s house and killed him. Since his mother stood up to them they killed her too.

Last night Juan David was faced with the following dilemma: avenge his best friend’s mother’s murder or refuse to take part in the retaliatory expedition and thus put his own life in danger. I tried to explain to him that the mother’s death wasn’t the worst thing that could’ve happened and that in fact she had averted years of terrible misery. He seemed convinced when he left.

When he got back for the make-up test this morning I found out his best friend’s mother’s murderer had been killed last night.

At the make-up test Anderson and Juan David met and checked each other out for the first time. They had both taken their shirts off so we could try out some scar-effects but they already each had at least five real ones. They also each have a large tattoo: a kind of iguana on Anderson’s back and a gargoyle on Juan David’s arm.

Execution

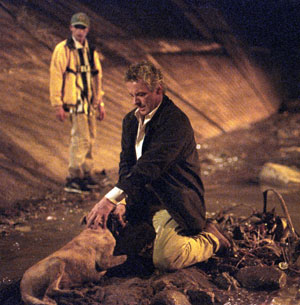

Papa Giovanni helps us enter the Diamante Commune. Yesterday, just after we parted company, he was having a beer with his friend Olman who, in the film, was going to play the part of the Attacker. A man slowly passed behind Olman and shot him in the head. He left just as slowly. The bullet, which could’ve wounded Giovanni, didn’t exit but it created a lump on Olman’s forehead before he dropped dead onto the table.

Giovanni is deeply grief-stricken, he can’t get over it.

Shooting postponed

We were supposed to start shooting this Sunday. We had planned it a bit too tight as the cameras, delayed by hurricane Floyd, only got here the day before yesterday.

The plane was forced to land in New Jersey, and the whole cargo stood idle in hangars for five nights while the town was flooded.

Upon the plane’s arrival in Bogotá the papers hadn’t come with the shipment which was stored overnight in a hangar.

The next day the thirty-four parcels were there but their weight didn’t correspond.

When we opened the crates three of them were empty: the two cameras, the large high-definition monitor and all the lenses (the best ones, the ones that are hardest to find) had disappeared.

Almost 200 000 dollars’ worth. The insurance will only reimburse 80 % of it. We might have to use part of the budget to cover the loss. We hope to be able to start next Sunday with lesser-quality lenses.

On the bright side: a bit more time to prepare.

The mystery: are the thieves American or Colombian and what project will someday be filmed with the equipment?

Second day

Fernando enters the America Church and sits down. The camera follows him from afar and from a very high vantage point to take in a life-size sitting Christ covered in bloody wounds. At the church entrance, a female beggar with a young child. It’s what I’d asked for only they’d forgotten about the child. It’s too late, we have to shoot before mass starts in half an hour. Eduardo goes out onto the street and brings me back a four year-old with his parents. They’ve dressed him in a nice white suit to take him to the doctor, all dolled-up, a real rich kid. Within minutes he’s wearing rags, covered with black make-up stains and before the eyes of his parents he’s transformed into a beggar at the side of a real beggar who scares him stiff. At the third take he covers his face with his hands and starts crying silently. A gripping image of pain. A nice shot. For the kid, a life memory.

In a corner I come across another fantastic, realistic sculpture of the Fallen Christ. I’ve been looking for this close-up, those eyes, for days, for the scene in which Fernando asks Christ to help him kill W. Mass begins, we quickly shoot the close-up—there’s a shiny spot on the nose of the bloody man on all fours, we ask the make-up artist to touch it up quickly .

Desechables

An incredible scene last night in the Church of San Antonio; we had fifty basuqueros come in, the local equivalent, but much worse, of crackheads. Some people here call them desechables or disposables, individuals you can throw away or kill, individuals you can do without. They’re wild-eyed and uncontrollable, talking and playing non-stop like small children. They sort of took over and we adjusted.

Before the shoot the wardrobe manager was taking pictures for continuity. One of the “basuqueros” appointed himself as their spokesperson to tell me that they were scared, that they thought we were drawing up lists to have them killed.

Locking themselves in the confessional booth to sniff glue from plastic bags. Sprawled on the ground to smoke. Candles and incense smoke all around. The camera takes a bird’s eye shot of all this and ends up exiting through the main door to fly up along the facade.

Juan David, who plays Wilmar, came by to see us. He’s very religious and cried out that we were all going to be excommunicated.

The church guard was worried that the priests, who had gone to bed at nine-thirty, would wake up and kick us out. Everything went well and we left the church cleaner than it had ever been. No one can believe what went on last night; it now seems it was nothing but a fantasy or a dream.

Morgue

Today the morgue, and to top it all off, not enough bodies to fill seventeen tables. T-shirts, sneakers and jeans are placed over the bodies for identification.

I’m not at all troubled—it astonishes me— being there and arranging the corpses as if they were extras. It only makes me feel like dancing and enjoying life more that same night.

Anderson paid us a visit. He wanted to see if there weren’t any friends of his on the tables. In any case there was one youngster with his jaw ripped off from a shotgun blast. He’d been killed the night before in a car, three buildings away from ours, right in front of the Bettencourt funeral parlor.

Shooting the scene in the subway

We paid a very high price to have a three-car train to ourselves for just a few hours of filming. We can only film the train while it travels in one direction, from one end of the line to the other. The return is just lost time. From time to time the train stops without warning, in the middle of nowhere.

The train can’t stop at stations—we have to stop shooting, interrupt it every time we pass through a station.

The scenery has to match. We tried to make a city version and a river-Communes version, and both of these categories with a sunny version and an overcast version. I don’t know if we have a really complete version for any of those.

Anderson isn’t concentrating.

The lights we had on hand didn’t work. We lost two hours replacing them and we had to install a generator in a mad rush in another car. This made the electrician taking care of it almost choke to death and set off a smoke alarm at the subway’s general headquarters. Another half hour to disconnect the alarm.Later the train got stuck for half an hour in a hangar at the end of the line with all the extras getting impatient about eating and going to the bathroom, another half hour lost because of all that.

The producer, Jaime Osorio, almost had a heart attack. He’d already had two, last year.

The worst: two kids in the scene didn’t want to act anymore and began to shriek so loudly we couldn’t hear the actors’ dialog. One of the children didn’t want to stay standing up on his seat, something that was essential for the scene.

A female subway worker was in charge of overseeing the scene. Eduardo took care of her but we had to be cautious so she wouldn’t notice the revolver or the screams.

Anderson’s culebras

Every day we find out something else and it isn’t him who tells us. There are people who have “debts to settle” (culebras) with him, in particular a serious affair with coke dealers from Manrique. They are suspected of having wanted to kill Anderson last night when they shot three of his best friends at the spot under the subway where he meets them every night; one dead and two injured. Luckily he wasn’t there, we were shooting that night. Before he started spending time with us he kept very nasty company.

There are also some policemen who know him very well and are just waiting to run into him alone at night to get rid of him. This is what they told Eduardo last week when they arrested Anderson in the street, handcuffed him and started beating him near Bolivar Park. It happened around lunch time, during the filming. Luckily Eduardo was able to radio the bodyguards and put an end to the incident.

The power of real weapons

After using very well-made copies, I found out that using real guns put my young actors into a trance. Their eyes shine, they’re much more concentrated and play their role much more seriously. This of course complicates the security issue but in some cases it’s worth it. I sometimes even go so far as to let them carry guns though they’re not visually used in the scene.

Cables and hoses

I often have to work slapdash so we don’t run even further behind schedule. It’s depressing. I’m starting to feel tired. Bit parts aren’t always well acted. Without a script girl there are many mistakes as far as continuity is concerned but the project’s originality is ineradicable. I now need to take hot baths to relax and be able to sleep a bit at night but it’s impossible. No one has ever taken a hot bath in any of my modern, luxurious, high-security apartment’s three sumptuous bathrooms. The small water-heater can barely fill the tub with an inch of hot water. So I bought thirty-five meters of garden hose to pipe hot water in from the kitchen at the other end of the apartment. All day I live and walk on black rubber tubing…electric cables, cables connecting the cameras to the monitors…

Pool hall scene

I found out just before shooting there that the pool hall I had chosen with the red walls and a Mary Help-of-Christians statue is actually an “oficina,” a place where you hire assassins. It is, according to my bodyguards, the best-known spot for this sort of transaction. And I’d asked the young regulars to be contacted as extras! A shoot that was supposed to be cut and dried ended up being very tense. We had to avoid at all cost that the boss or patrons overhear the dialog.

Anderson’s lack of concentration also caused a lot of problems.

We were also very lucky with the Dead Boy character. I didn’t know when I hired this boy to play Death-personified that he had two tattoos: a skull on his right shoulder and a Grim Reaper on the left. He’s in a rock band called “The Erect Penises.”

Yesterday

Last night two corpses on the first assistant’s doorstep, five blocks away from here in the rich, quiet Laureles neighborhood where we all live. The owner of a car and a thief had shot each other to death.

Yesterday our accountant was assaulted upon his return from the bank with an envelope full of cash. Two gun-slinging youngsters on a motorbike followed him from the bank and asked him to hand over the envelope. The accountant hesitated, they asked him if he wanted to die. It lasted all of two seconds in front of a dozen witnesses. They would’ve shot him without any hesitation—it’s one of their rules of conduct to maintain the level of danger and terror.

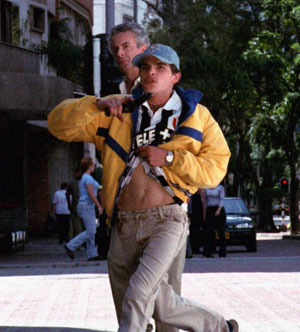

Gunshots on La Playa

Looking for peace and quiet we film violent street scenes as a rule very early on Sunday mornings. In front of the Fine Arts building there’s a shoot-out between Alexis and two guys who lose control of their motorcycle. They crash against a car and, as they fly through the air, they get pelted with bullets before falling dead on the roof of the car. I always try to avoid firing blanks in scenes so we don’t traumatize the population who already hear enough gunshots every day. Sometimes, though, it’s impossible to get good reactions from the extras without firing blanks. Such is the case for three shots that day. Soon after the first gunshots are fired, I see several people all dressed in white walking down La Playa Avenue where we’re filming. I immediately know they’re not extras. I’ve banned two colors in the film: white for technical videotaping reasons, and orange for aesthetic ones (which makes us have to unscrew or cover in gray the horrible orange-plastic trashcans that are hung throughout the city). For each take we reload the revolvers, add blood and when I turn around there are a few more people in white; they’re all walking in the same direction without stopping, observing us strangely. We finally figure it out: they’re Peace marchers.Today, for the first time, in every city in the country, crowds of millions of people in white are demonstrating that they’re sick and tired of violence. A memorable date.

When I was a child here it was also a matter of colors: the “blues” and the “reds” were killing each other by the thousands. We had to twist my parrot’s neck since it kept repeating: “I’m dressed in green but I’m a liberal” (red). We couldn’t give him away or let him loose: he might have caused a massacre in any house he would’ve landed in.

Erased scenes

Today the terrible news was confirmed: practically a full day’s worth of videotape was erased by mistake. Scene thirteen erased October 13th from the film’s thirteenth reel! It was a series of scenes in taxis and outdoor shots in the R. Commune where we’ll never be able to set foot again.

Yellow

Alexis’s death went rather well even though we had to wait six hours for the lights. The new, fun dialog in which Fernando and Alexis make plans to live abroad worked well, it makes the incident all the more surprising.

In spite of six attempts, the special effects people were unable to make the bullets explode in Alexis’s chest. We can’t afford to bring down the Mexican specialists. I’m lucky enough to be shooting digital and that in one take, during a botched explosion, a bit of blood accidentally ended up on Anderson’s face.

Once again the film’s color—yellow—worked incredibly well with Alexis’s blood-stained yellow windbreaker as his body was carried into a yellow cab under the yellow glow of the street lights. In the whole film there are hardly any outdoor takes that don’t include at least one yellow taxi passing by. The exit from the morgue at night, on the yellow-painted footbridge over the highway, with the Communes’ lights in the distance, is a magnificent shot made with almost no extra lighting. It’s a possible ending.

A new strategy

I found out last night from a police source that the guerillas have just put out a call for hostages in the criminal underground—they’ll pay a thousand dollars cash for any foreigner. A new strategy to replace that of the “Pescas milagrosas”(“miraculous catches”) which had fallen out of favor. A strategy similar to the one Pablo Escobar adopted eight years ago when he offered the same price for each murdered policeman. My bodyguards are very nervous. They can’t take it easy anymore.

Still, there was a “miraculous catch” the night before last on the road that joins the town of R. to the road to the airport. For once, the police tried to intervene: two dead among their ranks but only four people taken hostage.

The guerillas are among us, in the city, and they’re given a monthly salary (unemployment exceeds 20%). They steal vehicles, put on uniforms at the last minute, raise blockades, capture the hostages that interest them after having stripped the others of any valuables.They find out who is of interest to them on the spot using computers linked to the internet and take the selected hostages to some nearby place where other stolen vans are waiting to carry them off to mountainous areas in the jungle. In the best of cases, hostages are freed six to eight months later after several payments have been made. One thing is certain: taking into account the fact that, on every front, things are getting inexorably worse, this film could not have been made here a year from now. Unless there were a miracle, and peace took hold overnight. Nobody believes that will happen. Anyone who can is thinking of settling abroad.

God’s infamy

That’s what Fernando sees in the eyes of a small child sniffing glue. The child’s has just lost his mother two months before the filming of this scene . She sold basuco in the Barrio Triste for 300 pesos a dose (25 US cents). The gangs who control the trade decided to raise the price by 100 pesos(8 US Cents). She refused to make her customers pay more. Executed.

Yesterday we took a day’s break to make up for the previous sleepless night. So far it’s been the only day-long break from filming that I haven’t spent editing . I take advantage of the time off to take part in a great cavalcade on dream horses with twenty or so gentlemen from Antioquia. That is, in any case, what they perceive themselves to be. As cowboys as well, from a time when barbwire didn’t exist, free and lawless, but very religious. All the horses were branded with an ‘8.’ They belonged to one of the Ochoa sisters and her husband whom I got along with rather well, passing the aguardiente back and forth along the way. Two of the husband’s brothers were killed by the guerillas, another kidnapped. He told me how he came to oppose the paso fino (special colombian gait) because it isn’t a type of gait that a horse adopts naturally. According to him, it was an atrocity imposed by humans for their own comfort. He knew what he was talking about: until a few years ago, he was the biggest breeder of paso fino horses in the world.

Everyone’s dressed in fancy cowboy style. We stop for breakfast—a mixture of rice, plantain, fried pork skins and sausage wrapped and warmed up in a banana leaf served with beer and aguardiente. A magnificent view of the hills between La Ceja and Rio Negro, a relatively quiet region, controlled by the paramilitary, who are surely friends of the Ochoas or paid off by them. Several jeeps follow us anyway, full of men armed to the teeth (including mine with their mini-Uzis). None of the barbwire fences installed by the new landowners (investors from the city who do nothing with their land) stop us: one of the captains leading our party gets off his horse and cuts the fence wires with special pliers he carries on his belt next to his gun.

The fake Aiwa

We needed props, copies we could damage, an Aiwa sound-system to throw out the window. It turns out prices are so low that it’s three times cheaper to buy a real Aiwa sound-system than to have a fake one made.

A contraband Mont Blanc pen costs ninety dollars on the black market. The factory, the Mont Blanc headquarters, sold the same pen for 120 dollars. Money laundering.

I go buy my wine at this strange house bustling with people,a discreet family dwelling located in a working-class neighborhood next to ours. People run to it day and night to buy all kinds of alcohol at rock-bottom prices. Another money-laundering scheme.

A formula for filming downtown

–First of all, organize a fake set with cameras, projectors and a hysterical director. Comedy mixed with violence is a true crowd-pleaser. One of those mimes-beggars is the prefect stand-in for an actor. This afternoon, to distract an enormous crowd of onlookers, the violent comedy had social content; the delirious female crack-smoker who is in charge of finding five homeless people, crackheads or beggars every day as extras had a starring role, playing opposite the mime.

–Then very discreetly film the real thing fifty meters away.

–Coach a dozen extras to approach people who might notice what you’re doing during the takes. Have the extras ask them for the time or tell them to move along. The hapless souls who refuse to move are immediately assaulted by our special task-force: a group of frightening, stinking beggars who stick to them like glue and hound them for money until they leave.

This system works wonders. Unfortunately we still have to deal with the hot sun or the rain that alternately broil or soak the image, which means we sometimes have to finish up scenes in a hurry.

Rivers of blood in the Communes

Today was a memorable day spent in the Diamante Commune.

The electricians’ truck couldn’t make it to the location we had arranged high up in the neighborhood in order to get a view from above of the gigantic staircase. Lots of illegal cables—wired to steal electricity though it’s practically free in these neighborhoods—are hung so low across streets that a normal-sized truck can’t pass through.

The crew’s rendezvous site is loaded with memories for the Commune. An enormous mural of the WB logo (for Warner Brothers, very popular for its cartoons) remains riddled the holes from bullets which killed eight youngsters a year ago. The following day the revenge took place: twenty youngsters killed in the neighborhood above. A week ago the battle resumed and has once again become an all-out war: two murders the day before yesterday.

All the high-definition recording and transfer equipment is stored in the van which is always followed by two guards on motorcycles wearing blue uniforms and bullet-proof vests and carrying submachine guns. Today they were utterly terrified. With reason, said my jean-clad bodyguards, for these men were irresistible to groups who would kill in order to get ahold of weapons. Upon their arrival the men in blue could relax a bit as there were eight policemen dressed in olive drab and armed to the teeth, besides the five we are used to having with us. During the shoot, an old lady who was passing by told me that we were quite justified in having protection as there had been a lot of real blood spilled in the neighborhood and that it was a welcome change to see a little fake blood which she wouldn’t have to worry about.

The most impressive part of the scene was when we made it rain blood over the neighborhood. The special effects crew evidently made too much and we all got stained, our skin and clothes, with red ink that wouldn’t come off for three days. A normal movie rain shower that, at mid-take, starts coming down twice as hard and turns red. The sky, the earth, everything turns red and rivers of blood begin to flow everywhere. The quebrada (stream) turns red, all the kids start screaming for people to come out and see.

If I had known, I would’ve taken a wide shot instead of the close-ups of feet walking down steps and the rivers of blood that turn into Blood Lagoon. It’s my friend Luis Ospina’s team who has the best shots for the “making of” documentary. He was up in a balcony.

Everyone was moved by the image and symbolism of this conceptual “happening.” Especially the lady who lives in the house whose front part was transformed into blood headquarters. We mixed the water and the pigment in her yard. She’d lost two of her eight sons, one of them at the age of eighteen, the other at twenty-two, in the gun battles that continue to take place every night and that you can hear as distant echoes in the downtown area of the city down below. She said it must be a very sad moment in the film. I told her she had guessed right.

Hold up

We have an account at the Banco Popular in Laureles, our neighborhood. Yesterday there was a hold-up. Some young men asked the teller to open his till. He explained to them that the security system prevented him from doing so. They sprayed him with gasoline and since he still didn’t open it they lit him on fire. He died from his burns. No mention of this in the newspapers.

The angel-faced bodyguard is not what he seems

We hear he has connections with the paramilitary and, after a silly argument, he threatened to kill one of the crew members after the film was finished. The latter had to abandon ship—it was in his best interest. In order not to create a security breach one week before the end of the shoot, we’ve decided not to confront Leonardo who, this morning, before I’d found out about his threats, made me promise not to refuse to be a witness at his wedding next June with a seventeen year-old girl I met at the same time as he did. I remember that, back then, I’d begged the future fiancée to be wary of men.

Impotence and anger in the face of injustice.

The atmosphere is stifling.

The scene of drunkenness on the terrace at night

We’ve been waiting a week to shoot it when it isn’t raining. Right when the scene is starting to jell, incredibly loud music is heard from an outdoor concert. After fourteen hours straight of filming we can’t wait any longer, we shoot a few takes between songs. It starts raining, we stop. Technically we managed to finish the scene, but once again I’m frustrated, and so is the actor.

Tomorrow I’ll attempt a secret, commando-style filming at the cathedral as the religious authorities have refused to let us film there.

Only one more week of indoor shots left to do with a smaller crew.

Sleepwalking killers

Rohypnol is a kind of sleeping pill that was banned in Europe and the U.S. five or ten years ago. If you don’t go to sleep after taking it you can still function but forget absolutely everything you’ve done. You can find it anywhere here on the black market, in large quantities and cheap. I don’t know if the Roche company still manufactures them or if they’re copies.

It’s the assassins favorite drug as it allows them to feel unperturbed before and during a “job” and to forget about it afterwards. They call them “Roches” or “roaches” or “ruecas.”

Anderson, the kiss

Anderson coughs and spits all the time, very often out the window of the high-rise where we’re shooting. Rain of globs on the passersby. A week ago he started spitting blood, something that worried our main actor very much as he has to shoot a scene in which he kisses him on the mouth. Our main actor demanded medical tests. It proved impossible to get a hold of Anderson to obtain saliva and mucus samples on three consecutive days. Always out partying and never showing up at home. On one occasion he was two hours late for a scene. He’d spent the night with Juan David and fallen asleep at his place. It was when we called Juan David to shoot an unplanned scene that we finally got a hold of Anderson.

After we finally managed to drag him to the hospital three days in a row (tuberculosis tests negative), I had to show him myself how to kiss Germán; I also had to set up a situation where, at the moment of shooting, the crew all bet some money to dare him to do his kiss properly. When he saw the bills pile up he got self-conscious and was forced to do the scene. He collected over 200,000 pesos (100 dollars) which he then hid in the apartment. After smoking one of his enormous joints he forgot where he’d stashed it . It was too late to get in the apartment.

Last day

Our last day of shooting. We were supposed to start at 10 a.m. on a set built in a warehouse. The entrance hall of the morgue. Nothing is ready: a door and some fluorescent lights are missing. We wait around all day, and finally at 6 p.m. the door arrives. It’s too big. The lights have yet to be installed, we don’t have a tall enough ladder on hand. We end up filming at 9 p.m. with no fluorescent lights, only the regular film lights, a single very complex shot. It’s the last scene we’re shooting as well as one of the film’s last four scenes. We luckily never ran across these kinds of problems during the rest of the shoot. We just had to end it all on a slightly Colombian note. Overall, the crew I had the chance to work with were well up to international standards.

Emotions ran high when the champagne began to flow and things that had been left unsaid came out into the open: during the shoot, everyone had thought that I was totally crazy to have tried to make this film. Now they would have to return to the hard reality of a country on the brink of disaster without ever being able to forget these past seven weeks. Neither will I . I don’t think I will ever again take part in such an emotionally charged and dramatic shoot.

Driving home at 2 a.m. on the deserted highway I hear three gunshots at the back of the vehicle: one of my giddy bodyguards is firing into the air.

Later he will try to justify this by saying that a large car with six shady guys approached us at high speed and that he chased them away by firing. Eduardo is certain he didn’t see a car. I’m not so sure. We’ll never know. A typically Colombian experience: to become less and less sure how real what you see and hear is.

Dubbing

No recording studio available. We spend the whole night in my bedroom wich has been turned into a makeshift studio. Mattresses against the windows like an atomic bomb-shelter. Black tubing full of cables connect the tape recorder, microphone and television in my room to the Avid computer in the editing room at the other end of the apartment. Another black hose, running alongside the first, takes hot water from the kitchen to my fancy bathtub thirty five meters farther away. No one had been able to fill it with hot water until then.

Everyone—Anderson, Juan David, Germán and I—tries to make the magic of the shooting last for one more night; we all feel this experience has changed us in a profound way. Germán goes to pack his bags; he’s leaving in a few hours. I stay behind with Anderson and Juan David. They talk to me about the responsibility they suddenly felt when we started filming, the biggest responsibility of their lives, and one they weren’t expecting.

Nora’s sister assassinated

Nora’s sister (Vallejo’s sister-in-law) was assassinated by two men on a motorbike last week. They first wounded her; she managed to escape, and they caught up with her two blocks away. She was forty-two, always stuck to her principles and worked for the Envigado city administration. She was fighting against mob influences and had just been picked as a candidate for the upcoming elections in this municipality which had been in the hands of Pablo Escobar for a long time. The citizens are asking Nora to take her place. She is now beginning to receive threatening phone calls. She no longer excludes the option of leaving the country with her family, something unthinkable a few months ago.

Not far from Envigado, in R., we had our closing day party at a the “Lupus Dei” convention center—that’s how my chauffeur pronounces the organization’s name.

Eighteen musicians’ wages

The wonderful musicians at our closing day party — most of them elderly men who live very modestly and don’t have bank accounts, months sometimes going by before they get booked for a show — were dealt a hard blow today. Their boss went to the bank to cash our check. He went home with the eighteen musicians’ wages and on his doorstep got held up by young men who had followed him.

Christmas

Christmas is coming and everyone in town is obsessed with one thing: offering a nice Christmas celebration to their families. At any cost. And so the closer we get to this fateful date the more the crime rate will increase—to the point of doubling. It’s a tradition.

What also changes with Christmas is the evening soundtrack. I had gotten used to hearing gunshots every night, whether nearby or in the distance. They now blend in with an orgy of firecrackers which increases with every passing day.

The lighting is also excessive. Already, over the last two weeks, thousands of multicolored bulbs have been strung up in all of the city’s trees. I can’t help but think they might be the last lights we see for a long time. Over the last month the guerrillas have blown up forty-five electrical towers. Only ten have been rebuilt ; the others are in places that are too dangerous to get to. We’re on the brink of rationing or worse.

The Curia

Who will believe that we celebrated our closing day party at an Opus Dei convention center and that the apartment I’ve stayed in since the beginning of the shoot—and which we also use as an editing suite—belongs to the highest-ranking religious authority in the city? This morning they came to inspect the premises before my departure. My bedroom must have impressed them the most: above my desk a portrait and scapulars of Mary Help-of-Christians, the Blessed Lady of our film, and on the table, an enormous permanently lit candle with the same picture. There’s also a small polychrome plaster sculpture of a Christ on all fours covered in bloody wounds. Eduardo’s bedroom and bathroom are also full of pictures and candles, so much so that last week, for the day of the Immaculate Conception, our housekeeper and cook said to us: “I see that you like the Virgin very much, you’ll surely give me the day off then.”

The war is taking its toll: over 200 casualties in three days. The rationing of electricity has begun in poor neighborhoods.

Barrio Triste

I just had breakfast with Papa Giovanni who tells me what’s been going on in the neighborhood where he works as a mechanic. A war is being waged over the huecos ( the holes where basuco is sold and consumed) between the Montaneros and the Calenos. The latter are from Cali; they’re very well organized and have already taken over the Campo Valdéz Commune. Yesterday they went looking for one of the Montaneros in the depths of his “hole” and shot him six times in the chest. The man still managed to walk out onto the street normally, hail and get into a cab, and ask to be driven to the hospital. He died en route.

These guys walk around armed on street corners, go into bars and make themselves at home. Their favorite threat is: “Don’t bug me” or “Does someone feel like bugging me?” Two days ago one of them really got angry when an empty cab refused to stop after he had tried to hail it insistently. Furious, in front of witnesses, he killed the driver. Shortly afterwards, the back door of the taxi opened and a tiny man, the invisible passenger, got out of the car, scared senseless. Nobody said anything and the incident was viewed as a settling of scores. One more. Over the last week there have been one or two murders per day, all within a few of blocks of each other: what Giovanni calls the ravages of Christmas.

Christmas, yet

The editing room has a large balcony like all the other rooms in my apartment. Right across the street there are two banks. Yesterday, the housekeeper, who has plenty of time to look out the window, twice told us to come and see what was happening on the street. The first time it was a businessman getting into his white Trooper after having gone to the bank. Two young motorcyclists had grabbed an envelope from him. There was a visible commotion: all over the street people were talking about the incident which had only lasted a few seconds. Three minutes later everything was back to normal. But the law of series is the only rule to live by here. I had just managed to cut another minute from the film, which is now 1 h 47 min. long, when another distracting event took place: the same scenario only this time it was about two nuns and a small suitcase that had been stolen from them. Nothing stops the Chistmas fever, not even religion.

Firecrackers keep exploding all night, every night.

Cecilia takes care of the house-cleaning and the cooking. She’s very religious and very proper. As she often has nothing to do, she reads books like “How to know your son is taking drugs.” Her son is eight years old.

We need to drink a lot of coffee while we’re editing. Every time she brings us some she overhears some of the film’s scenes. Shootouts and insults, naked men—not always the same ones—in bed or kissing each other on the mouth. Tirades against the pope; the next day against Simón Bolivar or in praise of Pablo Escobar as a great employer of the people. Then more shootouts, bodies and bad language. And then yesterday, to top it all off, two men in bed and one of them says: “blessed be thou, Satan!” That’s when I saw her look really concerned.

It’s time to go do the rest of the editing somewhere else, before she starts telling her friends the priests about it.

Our favorite pastime: trying to figure out her take on the film.

A single regret

Not to have had the time before I left to meet a ballsy woman, the transvestite who rules over the poshest brothel in town with an iron hand– the whorehouse where people from the mafia rub shoulders with cops and government employees. A few months ago, during pre-production, I’d managed to make an appointment to have tea with her. I was curious to meet someone who must have quite an exceptional personality to be able to survive at the core of such a dangerous world while knowing everyone’s secrets. A character for Fassbinder. I’d been led down the secret hallway reserved for city hall employees and VIPs. It was directly opposite the main entrance, on the other side of the block, on a parallel street, and it opened onto a small, perfectly run-of-the-mill bar. At the far end, behind the bathrooms, a curtain covered the entrance to a maze that led to a reinforced door. There I was greeted by the chief of security who asked me to follow him. Another maze, then through the kitchen before emerging in a room full of very young girls and disco music. It’s 5 p.m.. Madam is late, I’m asked to wait for her. I hear she’s very busy — diversifying by launching a line of beauty products in Europe. She has several bodyguards. She usually comes in through the back entrance like I did.

The girls who pass by the main entrance often stop to hit a statue with a wooden spoon. It reminds me of something: Cali, twenty years ago. I walk over to get a closer look. It is indeed a seated Chinese Buddha. There’s a hole in its fat stomach. A drunken mobster fired a bullet into it, I’m sure of it; it’s something I’m familiar with. I check with the employees; it’s exactly what I thought.

In Cali, twenty years ago, Eduardo and I had accompanied a friend of ours to a brothel and I’d discovered a strange ritual which I thought was one of a kind: the girls hit a good-luck Buddha to punish it when there weren’t enough clients. It faced the wall and was forced to look endlessly at a bloody bullfighting painting. It had a hole in his fat tummy, and was surrounded by plaster replicas of Greek statues.

The clock soon strikes six, Madam has arrived she’s getting ready, she won’t be long but I have to leave for a casting meeting. I’ll be back.

Yes, but when? In a few months it’ll surely be more dangerous, and without proper bodyguards… Also the scandal the movie will cause in Colombia will make things very, very difficult for a long time.

– Barbet Schroeder